Be glad our Morgantown On the Mon monster is not a KRAKEN!

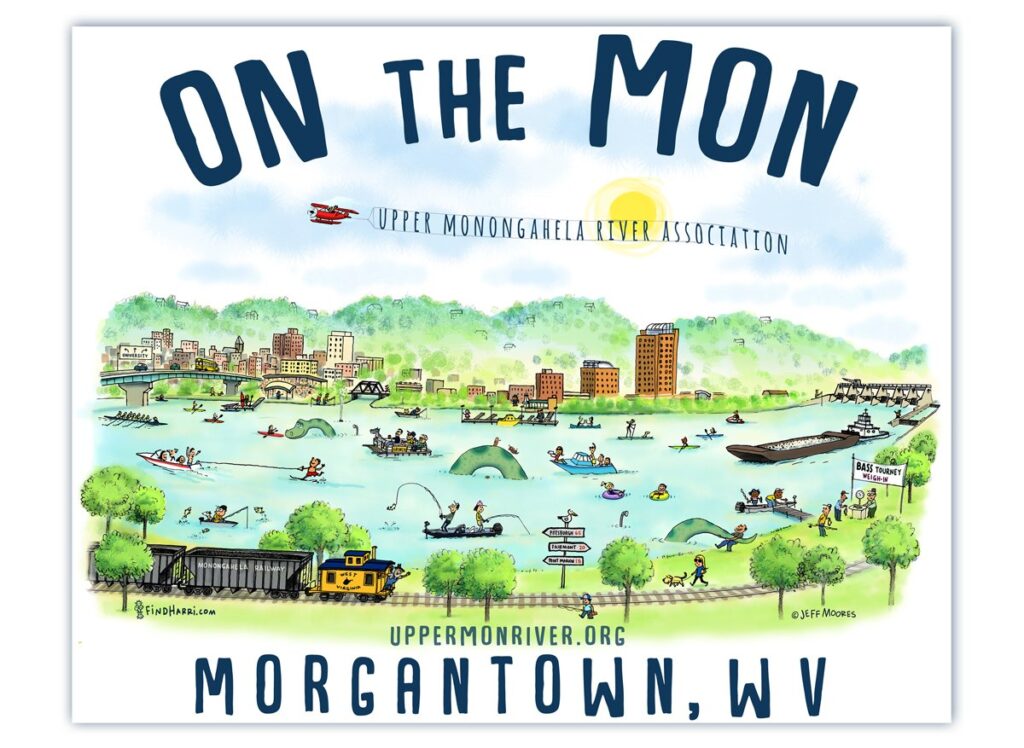

History about ON THE MON monster depicted in Jeff Moores artwork. First, look at article posted under IN THE NEWS on our Upper Mon River Association website, re three historical Mon monsters:

Do three legendary monsters inhabit the Monongahela River?

Lucky to be a river town, Morgantown has all kinds of fun flowing right alongside it. The Upper Mon River Association is celebrating that fun through a new print titled On the Mon. UMRA co-founder and power boat enthusiast Don Strimbeck commissioned the print, and lots of people in town will recognize the style of WVU grad and professional illustrator Jeff Moores. The design is also on T-shirts.

From his riverside home in Granville, Strimbeck filled us in.

Q: WHY COMMISSION THIS PRINT?

Don Strimbeck: UMRA’s goal is to stimulate interest in recreational boating and fishing on the Upper Mon in West Virginia. It is a wonderful experience to boat from Morgantown to Fairmont through the Morgantown, Hildebrand, and Opekiska locks. Or to boat north through the Point Marion and Grays Landing locks to the midpoint of the Mon at Fredericktown, Pennsylvania, dine at a Fredericktown restaurant, then return home. The Upper Mon in West Virginia is also very enjoyable for kayakers and for bass fishing tourneys.

Another major goal is to establish a full-service marina in the pool between the Morgantown and Point Marion locks. This is a vital need to facilitate Mon boating in the Morgantown area.

Q: WHAT IS THAT RIVER MONSTER IN THE PRINT?

DS: The monster is our Mon cousin of the famous Loch Ness monster in Scotland, and it occupies the Mon in addition to the Ogua, the Monongy, and the Rivesville River Monster that you may have heard of. Our monster is nicer and friendlier! We may hold a contest to name it.

Q: ANYTHING ELSE?

DS: UMRA is encouraging local businesses and organizations to use On the Mon in their own advertising to help publicize recreational activities on the Upper Mon. The front of a T-shirt could be their artwork, done by Jeff or another designer, and the back would be On the Mon. Contact UMRA to ask us about it.

Got your own boat? Then you’re all set this summer—you can launch at the bottom of Walnut Street, at Edith Barill Riverfront Park in Star City, or at the Fort Martin Boat Launch, among other spots.

If you don’t have a boat, check in with Morgantown Area Paddlers to ask about your options.

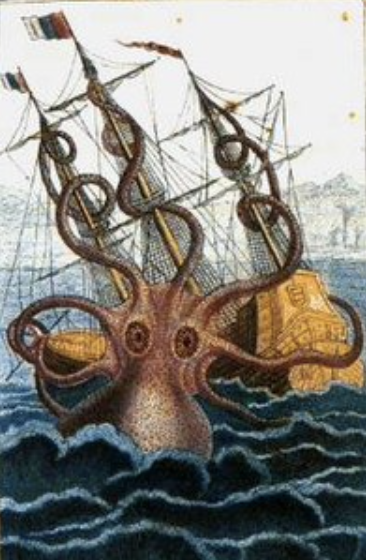

If you think our Morgantown Mon Monster is scary, be glad our river monster is not a KRAKEN!

Re-Releasing the ‘Kraken’: Mythical Beast of the Sea, Movies and Now, Election Disputes

An Old Norse word for a twisty underwater creature has surfaced in a Liam Neeson meme and a pro-Trump legal threat

Linguist and lexicographer Ben Zimmer analyzes the origins of words in the news. Read previous columns here.

When Merriam-Webster and Dictionary.com announced their selections for Word of the Year on Monday, it was not terribly surprising that both selected “pandemic” as the word that best summed up 2020, based on search traffic of their online dictionaries. But the runners-up include some more unexpected items. One word highlighted by Merriam-Webster is especially intriguing: “kraken.”

How did this name for a mighty, mythical Scandinavian sea monster become one of the most significant terms of 2020? The answer has to do with movie memes, professional hockey and electoral conspiracy theories.

Stories of the “kraken” originated in the tall tales told by sailors of a gigantic creature living in the waters off the coasts of Norway and Greenland. The word itself can be traced back to the Old Norse “kraki,” which became “krake” in Norwegian and Swedish, referring to something twisted or crooked. (“Crooked,” in fact, comes from the same source.) In the form “kraken,” the word got applied to twisty underwater animals both real and imagined. The kraken of Nordic legends was likely based on actual sightings of giant squid and octopuses, but folklore embellished it into a monstrosity capable of creating massive whirlpools and swallowing up even the largest ships.

The word “kraken” entered English in the mid-18th century thanks to translations of a natural history written by the Norwegian bishop Erik Pontoppidan, who described the beast in vivid detail. Stories of the kraken captivated the imagination of many writers, including Alfred Lord Tennyson, who titled an 1830 poem “The Kraken.” Tennyson imagined the Kraken slumbering in an “ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep” before awaking with apocalyptic fury.

The legend was likely based on sightings of giant squid and octopuses, but folklore embellished it into a ship-swallowing monstrosity.

Tennyson’s poem helped inspire a 1953 science-fiction novel by John Wyndham, “The Kraken Wakes,” about aliens from outer space who land in Earth’s oceans before launching attacks on humans. That same year, Captain Marvel battled a Kraken in an issue of Whiz Comics.

But the key pop-cultural appearance of the Kraken came in 1981, with the special-effects-heavy movie “The Clash of the Titans.” Screenwriter Beverley Cross spruced up Greek mythology by fancifully adding the Kraken to the mix. Whereas the original myth has Perseus saving Andromeda from the sea monster Cetus, the movie has Zeus (portrayed by Laurence Olivier ) issuing the command to Poseidon, “Let loose the Kraken!” Perseus then must battle the Kraken, “the last of the Titans,” memorably rendered in stop-motion animation.

When “The Clash of the Titans” was remade as a big-budget 3-D movie in 2010, Liam Neeson as Zeus gave the dramatic order, “Release the Kraken!” Even before the film was released, the trailer inspired countless Internet memes mocking Mr. Neeson’s over-the-top reading of the line.

Thanks in part to the success of those memes, the Kraken became such a prominent cultural icon that it beat out the competition as the name for Seattle’s new National Hockey League expansion team. When the franchise announced the team name of the Seattle Kraken in July, promotional materials connected it to the city’s maritime tradition and to the giant Pacific octopus species living off its shores.

The tale of the Kraken took another unlikely turn after the presidential election, as President Trump and his allies have continued to contest the outcome. Sidney Powell, a lawyer for former national security adviser Michael T. Flynn, claimed in a Fox Business Network interview that she would “release the Kraken” by revealing evidence of widespread electoral fraud. Since then, the phrase has become a rallying cry for pro-Trump groups, including QAnon conspiracy theorists, who have adopted it as a hashtag on social media. In a series of failed court filings, however, Ms. Powell’s “Kraken” has appeared less mighty than in the original myth.

URL:

Kraken vs. ship

STRIMBECK comment. How would you like to see a KRAKEN’s tentacles wrapped around the porthole of your room on your cruise ship, pulling the ship under!?

The kraken (/ˈkrɑːkən/)[7] is a legendary sea monster of enormous size said to appear off the coasts of Norway.

Kraken, the stuff of sailors’ superstitions and mythos, was first described in the modern age at the turn of 18th century travelogue by Francesco Negri, followed by Dano-Norwegian natural history writings. Egede (1741)[1729] described the kraken in detail and equated it with the hafgufa of medieval lore, but first description is often credited the Norwegian bishop Pontoppidan (1753). The bishop made an identification of the kraken as an octopus (polypus) of tremendous size,[b] and wrote that it had a reputation of pulling down ships, but the French malacologist Denys-Montfort of the 19th century is better known for these.

The great man-killing octopus entered French fiction when novelist Victor Hugo (1866) introduced the pieuvre octopus of Guernsey lore, which he identified with the kraken of legend, and this led to Jules Verne‘s depiction of the kraken, which he did not really distinguish between squid or octopus.

The legend may have indeed originated from sightings of giant squid, which may grow to 13–15 meters (40–50 feet) in length.

If Linnaeus wrote on the kraken, he only did so indirectly. Linnaues had published on the Microcosmus genus (a shield or canopy-like colony of various constituents), and counted several organisms under it, including Bartholin‘s description of the cetus type hafgufa, and Paullini‘s monstrous marinum, which are called “krakens” in works by other authors.[c] The claim that Linnaeus printed the vernacular name “kraken” in the margin of a later edition of Systema Naturae fails to be confirmed, and another claim that he published on the cephalopod species Sepia microcosmus[d] has been shown to be erroneous, though these continue to repeated as fact by modern-day writers.

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kraken

Giant squid

The giant squid (Architeuthis dux) is a species of deep-ocean dwelling squid in the family Architeuthidae. It can grow to a tremendous size, offering an example of deep-sea gigantism: recent estimates put the maximum size at around 12–13 m (39–43 ft)[2][3][4][5] for females and 10 m (33 ft)[3] for males, from the posterior fins to the tip of the two long tentacles (longer than the colossal squid at an estimated 9–10 m (30–33 ft),[6] but substantially lighter, due to the tentacles making up most of the length[7]). The mantle of the giant squid is about 2 m (6 ft 7 in) long (more for females, less for males), and the length of the squid excluding its tentacles (but including head and arms) rarely exceeds 5 m (16 ft).[3] Claims of specimens measuring 20 m (66 ft) or more have not been scientifically documented.[3]

The number of different giant squid species has been debated, but recent genetic research suggests that only one species exists.[8]

The first images of the animal in its natural habitat were taken in 2004 by a Japanese team.[9]

Range and habitat[edit]

The giant squid is widespread, occurring in all of the world’s oceans. It is usually found near continental and island slopes from the North Atlantic Ocean, especially Newfoundland, Norway, the northern British Isles, Spain and the oceanic islands of the Azores and Madeira, to the South Atlantic around southern Africa, the North Pacific around Japan, and the southwestern Pacific around New Zealand and Australia.[10] Specimens are rare in tropical and polar latitudes.

The vertical distribution of giant squid is incompletely known, but data from trawled specimens and sperm whale diving behavior suggest it spans a large range of depths, possibly 300–1,000 metres (980–3,280 ft).[11]

How does a giant squid propel?

It draws water into its mantle cavity by expanding its muscles. The mantle stretches like a rubber band, then contracts and forcibly pushes the water out through the funnel. The squid shoots backward, tail first. When escaping from a predator, a squid can propel itself as quickly as 25 body lengths a second.

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giant_squid

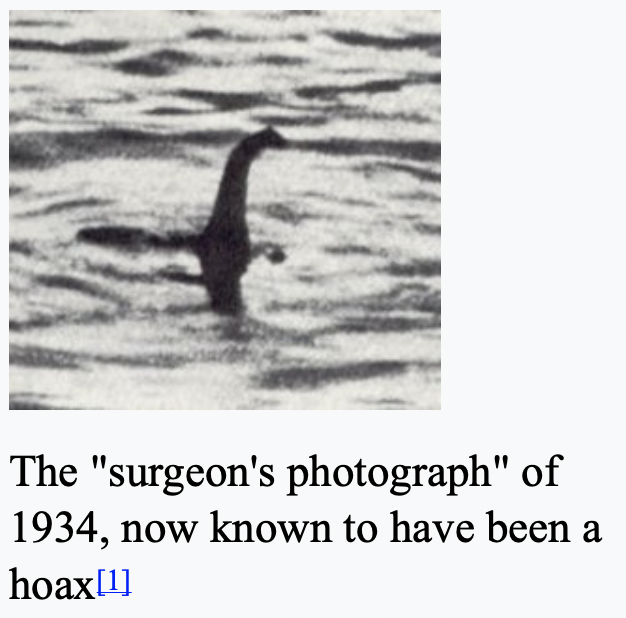

Loch Ness Monster

Loch Ness Monster (Scottish Gaelic: Uilebheist Loch Nis[3]), affectionately known as Nessie, is a creature in Scottish folklore that is said to inhabit Loch Ness in the Scottish Highlands. It is often described as large, long-necked, and with one or more humps protruding from the water. Popular interest and belief in the creature has varied since it was brought to worldwide attention in 1933. Evidence of its existence is anecdotal, with a number of disputed photographs and sonar readings.

The scientific community regards the Loch Ness Monster as a phenomenon without biological basis, explaining sightings as hoaxes, wishful thinking, and the misidentification of mundane objects.[4] The pseudoscience and subculture of cryptozoology has placed particular emphasis on the creature.

Origin of the name

In August 1933, the Courier published the account of George Spicer’s alleged sighting. Public interest skyrocketed, with countless letters being sent in detailing different sightings[5] describing a “monster fish,” “sea serpent,” or “dragon,”[6] with the final name ultimately settling on “Loch Ness monster.”[7] Since the 1940s, the creature has been affectionately called Nessie (Scottish Gaelic: Niseag).[8][9]