NOTICE — Millions of gallons of briny, toxic, wastewater from shale gas drilling and fracking operations could soon be loaded onto barges and pushed down the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio rivers.

A loose network of river tank terminal and barge companies has floated plans to begin shipping wastewater containing petroleum condensates, cancer-causing chemicals and radioactive material, between as many as seven river terminal sites spread out over hundreds of miles of the region’s major waterways.

The barging of wastewater on rivers has been discussed for at least a dozen years, but like a tow on a sandbar, the industry initiative has been repeatedly sidelined due to permitting issues, environmental concerns and the risk of contamination of public water supplies that draw from the rivers.

Although shale gas well drilling and fracking have been in a trough due to low natural gas prices, interest in barging wastewater has rekindled in recent years as transport and disposal of the mixed liquid wastes have become costlier for the drilling industry.

In meetings, letters and emails with regulators, barge companies and terminal owners have pressed regulatory agencies to issue authorizations, approvals and permits. And drilling industry publications are touting the public safety and economic benefits of moving wastewater by tanker barge.

Last month, in the first publicized acknowledgement that the idea of wastewater barging is starting to move again, Belle Vernon-based Guttman Realty Co. received a grant of almost $500,000 from the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development’s Commonwealth Financing Authority to retrofit the existing tank and barge loading terminal along the Monongahela River in Speers, Washington County, 43.5 river miles above Pittsburgh’s Point.

The changes would allow the Speers terminal to accept tanker truckloads of wastewater, also known by the shale gas industry term “produced water,” according to an April news release touting the grant from State Rep. Bud Cook, R-Belle Vernon.

“The facility will be modified,” the release stated, “to accept waste water from the natural gas industry by truck to be stored in existing tanks and ultimately transported by barge to the treatment facility in Ohio.” Using barges to transport wastewater also will reduce truck traffic, diesel exhaust, truck-auto collisions and road damage, the release stated.

But multiple environmental organizations from the tri-state area have strong concerns and many questions about those plans, saying river wastewater transport is poorly regulated and increases risks of chemical and radioactive spills, and those spills can contaminate waterways that are drinking water sources for millions of people, and, increasingly, recreational venues.

They say drilling and fracking wastewater contains salty brines, drilling and fracking chemicals and naturally occurring radioactive material flushed from shale formations thousands of feet underground. Radium-226 and radium-228, both found in brine waste, are known carcinogens and can cause bone, liver and breast cancer in high concentrations, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The wastewater can also contain other radioactive components, including Potassium 40, Thorium 232, and Uranium 238.

“Our Three Rivers are going to become the grand speedway of fracking waste,” said Gillian Graber, executive director of Protect PT, a local Pennsylvania environmental organization. “All three of our major waterways could be impacted by a spill or release of fluids. Spills are scary, but the build-up of small releases is also a major concern.”

Sarah Martik, campaign director at the Center for Coalfield Justice, said in an email statement that barges are unreliable and the fracking wastewater is “extremely hazardous. It is irresponsible to turn the Mon Valley into a funnel for regional fracking waste, just as it’s irresponsible to barge the waste down the river,” Ms. Martik said. “How many tons of coal are sitting at the bottom of the river from barges that have sunk in the past?”

The Monongahela River alone serves as the main source of water supply for some 850,000 residents in the Pittsburgh metropolitan region. And most of the drinking water for the city of Pittsburgh comes from the Allegheny River.

Other sites part of overall plan

In addition to the terminal at Speers, four other barge loading sites were identified in documents provided by the U.S. Coast Guard in response to a Freedom of Information Act request by the Fresh Water Accountability Project, an Ohio environmental organization that focuses on water protection and shared them with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

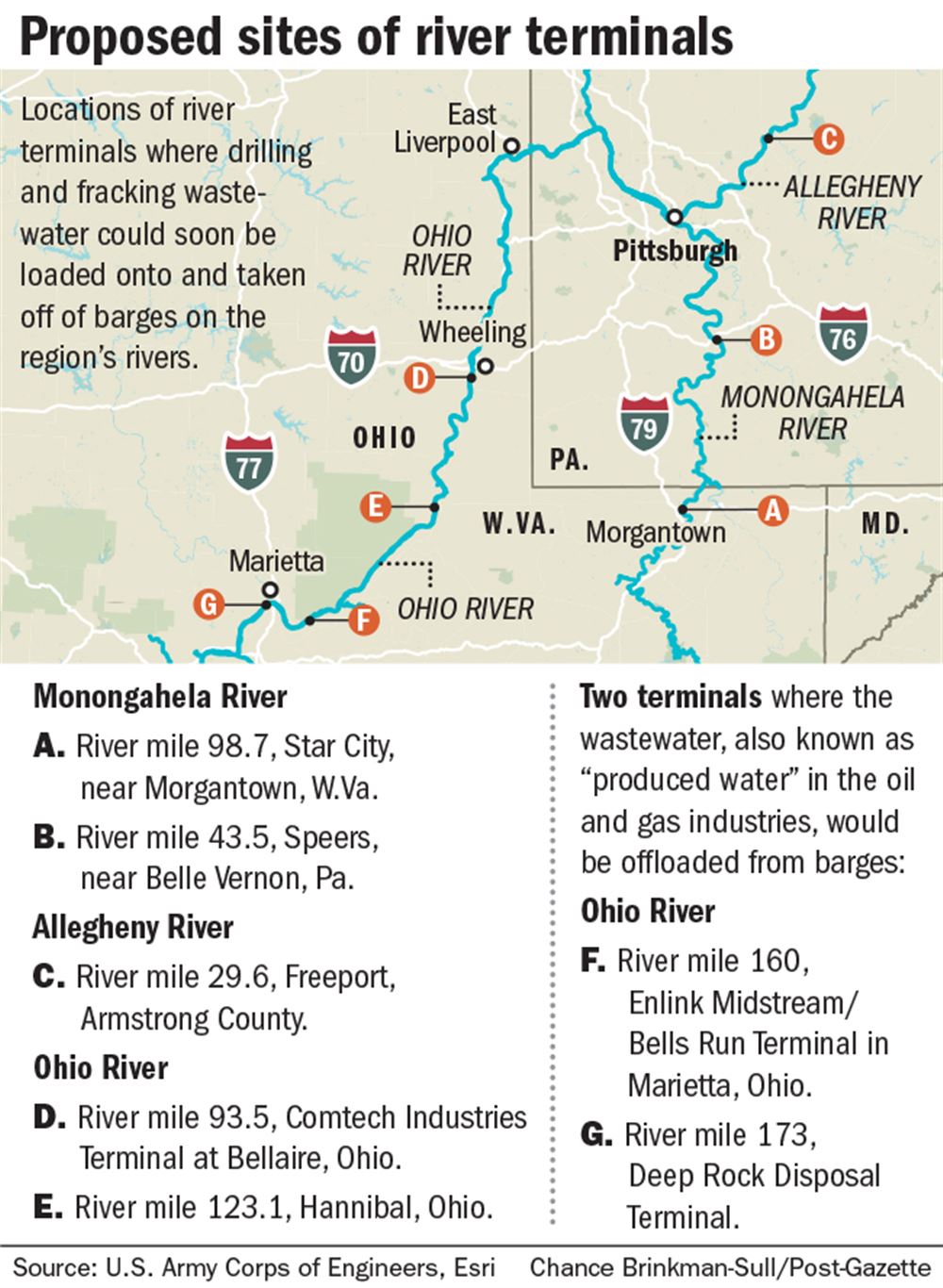

Those loading terminals include another on the Monongahela River at Star City, near Morgantown, W.Va., 98.7 miles upriver from Pittsburgh; and two on the Ohio River, at Bellaire and Hannibal, Ohio, 93.5 miles and 123.1 miles downriver from Pittsburgh.

A fifth wastewater loading facility option is identified as the Nicholas Enterprises Inc. terminal in Freeport, Armstrong County, 29.6 miles up the Allegheny River from Pittsburgh, and 20 miles from the Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority’s water intake pipes at Aspinwall.

According to a November 2019 U.S. Coast Guard cargo authorization form, the plan at the time was to barge wastewater to unloading terminals owned by Enlink Midstream at Bells Run near Portland, Ohio, and DeepRock Disposal Solutions, LLC, in Marietta, Ohio, located 160 and 173 river miles, respectively, from Pittsburgh.

Houston-headquartered DeepRock, a business partner with Comtech Industries, owner of the Bellaire terminal, operates 12 deep disposal wells at five sites near the unloading terminals in Ohio and can accept up to 50,000 barrels or 2.1 million gallons of wastewater a day.

A Dec. 22 article on Comtech’s webpage states that DeepRock had received more than 30 permits and authorizations, is in “conversation” with river terminals on all three rivers, and is expected to begin receiving wastewater and unloading barges at its Marietta terminal during the first quarter of this year. A day later, a headline in Marcellus Drilling News, an industry website, stated, “Barging Fracked Wastewater on Ohio River Approved! Starts in 1Q21,” referring to the first quarter of 2021.

But barging wastewater has not started yet, and Dean Grose, chief executive officer at Comtech, did not respond to requests for information about how that timeline has changed, what has caused the delay, or Comtech’s or DeepRock’s current plans for wastewater barging.

Taylor Grenert, Comtech marketing coordinator, cited nonspecific permitting issues when asked about the delay, but added that terminal facilities are “ready to go.”

One possible snag may be due to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, which has had sporadic interactions with Guttman Realty, part of the multibillion-dollar Guttman Group, dating back more than a decade about using its river terminals to ship wastewater.

Most recently, on a June 2020 conference call with regulators from the DEP’s Southwest Region office, Guttman representatives raised the possibility of using the Speers bulk liquid storage terminal to receive, store, process, and transfer natural gas produced water to barges for out-of-state disposal.

But Lauren Failey, a DEP spokeswoman, said in an email response to questions that the company hasn’t applied for a residual waste transfer facility permit, which would be required for such a facility. She also said the DEP doesn’t regulate what is transported on the rivers.

James Lee, a spokesman for the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, said the state doesn’t require a permit to transfer residual waste like Pennsylvania. “While the facility may have existing permits or need additional permits from DEP for various activities, the act of shipping wastewater by barge from unconventional gas development in and of itself is not something that requires a DEP permit,” Ms. Fraley said.

Another snag is that Guttman, which didn’t respond to many interview requests during the past two weeks, sold its terminals in Star City and Belle Vernon, both on the Monongahela, to Zenith Energy Terminals PA Holdings LLC in January.

A water obstruction and encroachment permit was transferred to Zenith in April 2021. New permits would be required if Zenith chooses to modify the terminal facilities, Ms. Fraley said, but DEP has not had discussions or received any application.

Jay Reynolds, Zenith’s chief commercial officer, said none of the company’s terminals handle drilling wastewater, there are no plans to do so and it’s “not a business we are pursuing.”

Casey Smith, a spokeswoman for the state Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development, said the department was told by Guttman that it would take six to eight months to get the DEP residual waste transfer permit, and must have all permit approvals before funds are disbursed.

“Should the company fail to obtain a permit from the DEP, they would be unable to draw down any funds and the grant would be liquidated,” Ms. Smith said.